AncestryDNA® Traits

Cavities

As a kid, were you more likely to get cavities than your friends? Or maybe you were one of the lucky (and rare) ones who never had to get a cavity filled.

While oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups play a big role in whether you develop cavities, your genes could also be a factor in battling tooth decay, even if you brush and floss regularly.

Discover if genetics might be behind your tendency to develop cavities. With a simple AncestryDNA + Traits, you can learn about your proneness to cavities and other traits like hangryness and being a picky eater.

What Causes Cavities in Teeth?

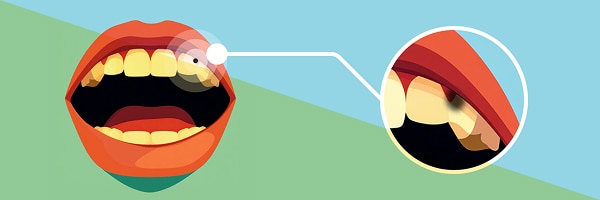

Dental caries, or cavities, can be caused by several factors. Mainly, it’s because of tooth decay. When the mouth’s natural microbes, like bacteria, consume sugars and starches from food particles, they leave behind waste. That waste can be in the form of a film that covers your teeth, called plaque. Bacterial waste can also include acids that dissolve tooth enamel and leave holes in the teeth. When teeth aren’t regularly cleaned, plaque can harden into tartar, becoming a sort of shield. Behind that barrier, the acids can proceed to weaken tooth enamel, worsening any already present damage and decay.

Several factors can exacerbate tooth decay. Some of the most common ones include:

- Sugary snacks or beverages

- Not getting enough fluoride

- Dry mouth

- Heartburn and acid reflux

Developing cavities is incredibly common. In fact, untreated cavities in permanent teeth are the most common health condition worldwide.

Fortunately, cavities are highly preventable with a few simple dental care steps.

- Brush your teeth twice per day for two minutes.

- Floss every day.

- Use fluoridated toothpaste.

- Drink fluoridated water.

- Minimise consumption of juice and sugar-sweetened beverages./li>

- See your dentist every six months for checkups and preventive treatments.

- Don't smoke; it tends to dry out the mouth, making your teeth more susceptible to decay.

Are Cavities Genetic?

While cavities themselves aren't inherited, the tendency to develop them appears to be influenced by genetics. Inherited factors, such as enamel health and strength, the shape and alignment of teeth, and the flow of saliva, could make someone more likely to develop cavities.

To explore the connection between cavities and genetics, the AncestryDNA team asked 760,000 people, “Have you ever had a cavity?” By comparing their responses to their genetic profiles, Ancestry scientists also found that the genetic basis of this trait is very complex; there are at least 750 genetic markers related to cavities. The team used these results to develop a polygenic risk score—a statistical tool used to determine how likely you are to have a trait based on your genetics. In the end, though, the team found that only about 3% of the difference in whether people developed cavities could be explained by differences in their genetics—also known as the heritability.

So, while there's definitely some genetic influence on cavity proneness, the development of cavities can mostly be controlled by hygiene habits, diet, and access to healthcare.

What Else Does Science Say About Getting Cavities?

Dietary and oral hygiene habits play a major role in cavity development. According to a Polish study on 12-year-olds, those who drank sweetened carbonated drinks daily had a much higher chance of developing cavities than those who didn't. Likewise, children who didn't brush their teeth daily were more likely to develop cavities than those who did at least once per day. A Chinese study of preschool-aged children revealed similar results, citing high sugary food or drink consumption and frequent snacking as common factors in those who developed cavities.

Another reason people develop cavities is having a condition called dry mouth (xerostomia). This can occur as a common side effect of certain medications, such as antihistamines, decongestants, and antidepressants. However, some people experience this due to frequent mouth breathing. Having a dry mouth means that there isn’t enough natural saliva to wash away food debris and neutralise acids produced by bacteria, which increases the risk of cavities.

Whether or not someone has access to fluoride treatments can also influence cavity development. Fluoride helps stop tooth demineralisation while promoting remineralisation. It also reduces the growth of plaque bacteria. Adding fluoride to drinking water can reduce cavities in children by 40-70%, making it a highly effective solution.

Historical Treatments for Cavities

Long before electric drills and various filling types became commonplace, people discovered that tooth decay must be carved out to prevent it from spreading and causing further pain.

Historical evidence of tooth decay—and treatments—can be found in the skulls of early humans. Archaeologists have identified a skeleton from 13,000 years ago containing teeth with signs of dental fillings. The person's front teeth showed holes that included signs of scraping and twisting of some sort of handheld tool. Traces of bitumen, a tar-like substance known for its antiseptic properties, were found within the cavities, suggesting early forms of dental treatment.

In China, as far back as the early 1400s, people treated cavities with a mixture of arsenic and vinegar. It's likely this practice aimed to kill the dental pulp tissue within the tooth, which would eliminate pain.

Curious about whether you've got the genes that make you more prone to cavities? Wondering where you got your flat feet, dimples, or wisdom teeth? An AncestryDNA + Traits test highlights all sorts of genetically influenced appearance, personality, and performance traits. If you've already taken your test, check out your results today with an your Ancestry membership.

References

-

“5 Amazingly Simple Things You Can Do to Prevent Cavities.” 23 October 2017. College of Dentistry, University of Illinois, Chicago. https://dentistry.uic.edu/news-stories/5-amazingly-simple-things-you-can-do-to-prevent-cavities/.

Andrysiak-Karmińska, et al. “Factors Affecting Dental Caries Experience in 12-Year-Olds, Based on Data from Two Polish Provinces.” Nutrients. 6 May 2022. doi:10.3390/nu14091948.

“Cavities and tooth decay.” Mayo Clinic. Accessed 3 July 2025. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cavities/symptoms-causes/syc-20352892.

Cheng, Feng-Chou, Yin-Lin Wang, et al. “The evolution of arsenic-containing traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions for treatment of toothache due to tooth decay.” Journal of Dental Sciences. 3 December 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2023.11.015.

Cogulu, Dilsah and Ceren Saglam. “Genetic aspects of dental caries.” Frontiers in Dental Medicine. 1 December 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdmed.2022.1060177.

Daley, Jason. “13,000-Year-Old Fillings Were “Drilled” With Stone and Packed With Tar.” Smithsonian Magazine. 11 April 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/researchers-find-filling-made-stone-age-dentist-180962845/.

“Dry Mouth (Xerostomia).” Cleveland Clinic. Accessed 3 July 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10902-dry-mouth-xerostomia.

Harrison, Rachel. “The Facts—and Largely Unfounded Fears—of Fluoride.” New York University. 21 January 2025. https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2025/january/facts-and-fears-fluoride.html.

“Health Literacy in Early Childhood Newsletter: Oral Health.” New York City Department of Education. January 2021. https://dental.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyudental/documents/faculty/pediatrics/Health-Literacy-Newsletter-January-Oral-Health-NYCDOE.pdf.

Kobierska-Brzoza, Johanna and Urszula Kaczmarek. “Genetic Aspects of Dental Caries.” Dental and Medical Problems. September 2016. DOI:10.17219/dmp/62964.

“Mouth Microbes: The Helpful and the Harmful.” National Institutes of Health. May 2019. https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2019/05/mouth-microbes.

“Oral health.” World Health Organization. 17 March 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health.

Xu, Hua, Xiaolan Ma, et al. “Exploring the state and influential factors of dental caries in preschool children aged 3–6 years in Xingtai City.” BMC Oral Health. 16 August 2024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04663-2.